The horse occupies a central position in American culture and folklore and is inextricably linked with the pioneers of old, cowboys, the Wild West and the freedom of the plains. Furthermore, the image of wild mustangs roaming North America’s vast open spaces is familiar to all.

But where do horses come from? Where did they evolve? And how did mustangs come to establish themselves throughout their North American range? To give you the answers you are looking for, here we discuss the question, are horses native to North America?

If you want to learn more about America’s free-roaming mustangs, you can also check out this documentary before reading on.

The evolution of horse ancestors in North America – the earliest beginnings

Whether horses are native to the Americas is a more complex and contentious question than it might first appear, but one thing that’s certain is that the ancestors of today’s horses evolved in North America.

Modern horses, along with donkeys and zebras, belong to the genus Equus, the only remaining genus of a larger family of animals known as Equidae.

Over millions of years of evolution, many other genera (the plural of “genus”) of Equidae appeared and went extinct, but nowadays, Equus is the only genus that survives.

Among the very oldest members of the Equidae family – and a distant ancestor of today’s horses, donkeys and zebras – is a creature called eohippus.

Its name means “dawn horse”, and this ancient progenitor of modern horses is known from early Eocene deposits, mostly found in the Wind River basin in Wyoming, meaning it first appeared around 52 million years ago.

However, eohippus would not have looked very much like what we think of as horses today. It was only about the size of a fox and had toes on all its feet – although rudimentary hooves were beginning to develop.

Eohippus probably lived in forests, eating soft foliage and fruit, and it already displayed certain adaptations for speed such as long legs relative to the size of its body.

The appearance Equus

Over many millions of years, the descendants of eohippus evolved, eventually giving rise to the genus Equus, probably around 4 million years ago. These early Equus species were still not modern horses, but by now, they were much closer to what we would recognize as a horse.

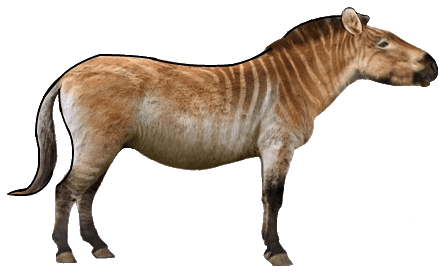

One of the earliest Equus species, Equus simplicidens – commonly known as the Hagerman horse –appeared around 3.5 million years ago and was first discovered in fossils in Hagerman, Idaho, in the early 20th century.

The Hagerman horse probably resembled a stocky modern zebra with a donkey-like head.

Migration to Eurasia and Extinction in the Americas

Animals like the Hagerman horse thrived in North America, and at some point around 2-3 million years ago, some of them also crossed into Eurasia, presumably traversing the Bering land bridge.

From then on, it is thought that members of the Equus genus crossed back and forth between North American and Eurasia several times.

The populations in North America are also thought to have gone extinct several times before animals returning from Eurasia repopulated the continent.

The final extinction in North America probably occurred around 13,000-11,000 years ago, and if members of Equus hadn’t crossed into Eurasia, the genus would have become completely extinct.

Domestication and return to the Americas

According to the most widely accepted version of the story, the modern horse, Equus ferus caballus, the descendant of animals that crossed the Bering land bridge, was probably first domesticated in Central Asia sometime before 3500 BCE.

From there, domesticated horses spread rapidly throughout the Eurasian continent, playing an important role in many cultures.

Later, when Spanish explorers reached the Americas, they brought horses with them.

The first Spanish horses were taken to the Virgin Islands by Columbus in 1493 on his second voyage, after which they were also brought to the American mainland, starting in 1519.

It is thought that some of those horses managed to escape or were stolen, and these feral horses then went on to populate parts of North America. The descendants of these animals make up the bulk of today’s herds of American mustangs.

The “native” vs “introduced” controversy

There are now probably around 90,000 free-roaming mustangs in the United States, and although they are often referred to as “wild” horses, since they are descended from the domesticated stock that arrived with the Spanish, they should technically be termed “feral”.

However, a certain amount of controversy surrounds their status, and the debate hinges on whether the reintroduced domesticated Spanish horses can be considered the same species as those that went extinct in North America around 13,000-11,000 years ago.

It used to be accepted that, although they belonged to the genus Equus, the horses that went extinct in North America belonged to various species that were distinct from Equus ferus caballus – and the fossil record appeared to back this up.

In the past, when paleontologists looked at the fossils they unearthed, they classified the animals according to their physical properties. This is the traditional methodology, and it’s a logical way of working since paleontologists often had little other evidence to go on.

Among many examples would be the species Equus lambei, commonly known as the Yukon horse. Due to apparent physical differences between this animal and modern horses, the Yukon horse was classified as a separate – although closely related – species.

The same is true for other extinct species of Equus, and the established view was that the animals represented in the North American fossil record were not the same species as the modern horse.

Arguments in favor of horses being a native species

More recently, researchers have begun to use modern technology – specifically, techniques looking at mitochondrial DNA – to shed more light on the subject, and the results have thrown the previously accepted theory into doubt.

For example, researcher Ann Forstén, of the Zoological Institute at the University of Helsinki, looked at the mitochondrial DNA from the frozen carcass of a Yukon horse and found it to be much more closely related to the modern horse than was previously expected.

Although the Yukon horse had certain physical characteristics that you don’t find in modern horses, genetically, it was close enough to be considered to be the same species as the modern horse. The two are just subspecies of the same type of animal.

Why is that important?

Let’s take another example to illustrate what this means.

If you think of the modern domesticated dog, there is a wide variety of different breeds in the world today. They come in all shapes and sizes, from something large and powerful like a rottweiler to something small and delicate like a chihuahua.

If a paleontologist of the distant future were to unearth fossils of rottweilers and chihuahuas, without any other information and just judging on the physical appearance of the two animals, they would most likely be considered different species.

However, we know that they are merely different breeds – or subspecies – of the same animal. Genetically, they are extremely similar.

So based on the new information gleaned from DNA analysis, some people now believe that the Yukon horse and the modern domesticated horse belong to the same species – they are merely two closely related subspecies.

This has an important implication because if we accept this view, then this species already existed in the Americas well before the Spanish arrived. This means the Spanish were simply bringing back an extinct local species rather than introducing a new one.

Why does it matter?

Some people might consider this whole discussion rather abstract and academic. After all, what does it matter if the modern domesticated horse is a different species or just a different subspecies from the horses that existed in North America before they went extinct?

However, it isn’t just a question of names and classification because this debate also has a bearing on the real world.

In the US, government agencies are required to look after native species by protecting them from invasive, non-native species that may harm them – and generally speaking, this involves reducing numbers of or even eradicating species deemed to be non-native and harmful.

As a result, whether we classify free-roaming horses in the US as a returned native species or as an introduced non-native species has a tangible effect on how they are treated.

So far, the issue hasn’t been fully resolved. Currently, mustangs are still considered a non-native species. However, their cultural significance in the United States is recognized, so they are tolerated and protected to an extent, although populations are managed.

At the same time, some argue that since mustangs are essentially the same species as the extinct North American horses, they should be given the same status and protection as other species that are native to North America.

“Wild” vs “feral” vs “domesticated”

At least part of the argument comes down to the differences between what we call “wild” animals, “feral” animals and “domesticated” animals.

In theory, the definitions are clear. A wild animal is an animal whose ancestors have never been domesticated while a feral animal is one that is descended from domesticated animals that have escaped back into the wild.

But what is a “domesticated” animal?

To answer this question, it’s useful to think of the differences between a captive zebra in a zoo and a domesticated horse – because “domestication” and “captivity” are two different things.

Captive zebras are still wild animals, even if they are born into captivity from captive parents. Occasionally, it might be possible to find a zebra that can be tamed and may even let you ride it, but with most zebras, riding them is impossible due to their temperament and physiology.

Domesticated horses, on the other hand, have been selectively bred over many generations to favor certain characteristics, including docility, calmness of temperament, willingness to be ridden and, in some breeds, willingness to work.

(That’s not to say that the original wild horses of old were all unrideable – it just means that domesticated horses have been selectively bred to make riding them more amenable to being ridden.)

The same can be said about domesticated dogs and wolves. You can’t keep the offspring of captive wolves like you would a pet dog – even though it was born into captivity, it’s still a wild animal.

The question, then, is how much has the domestication process and millennia of selective breeding changed the horse and how much do modern domestic horses differ from their truly wild ancestors?

Are there any truly wild horses anywhere in the world?

Perhaps one way to approach this question would be to look at wild – as opposed to feral – populations of horses to see how they differ from domestic horses. But do such animals still exist? Well, maybe.

One candidate, known as the tarpan, lived in the wild until the recent past, with the last known individual dying in captivity in 1909. These animals roamed the Russian steppe in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it is still debated whether they were truly wild or merely feral.

Another possibility is the so-called Przewalski’s horse. This animal was previously declared extinct in the wild, but captive animals remained, and they were reintroduced into the wild in the 1990s.

However, even with these animals, once thought to be the world’s last remaining truly wild horses, genetic analysis shows that they may actually be related to ancient domesticated horses, so it’s possible that now, no truly wild, never-domesticated horses still exist.

This means we may never know how much the years of domestication altered the wild horse in terms of physiology and temperament before it came into contact with humans.

However, the natural ability of mustangs to revert to a wild way of life suggests that a certain amount of “wildness” remains in the species.

Are horses native to the Americas? Yes and no

So we can see that the question of whether horses are native to North America is not as simple as it might seem. Horses once existed in the Americas, this much is certain, but they probably went extinct sometime around 13,000-11,000 years ago.

They were then reintroduced by the Spanish, and the main debate now centers on how much these animals differ from those that were present before their extinction in North America, and this is a question that remains unanswered.

wow this article really helped me to know a lot about this horse

This was very thorough and interesting.

Really enjoyed this article, went in just knowing horses weren’t native to modern America prior to columbus and came out with a lot more knowledge than expected. Weird that the US government doesn’t treat horses as a native species, their cultural and historical significance to settlers and native Americans alike along with the DNA evidence should classify them as native animals if you ask me.

It was really interesting to learn more about mustangs and not only. Great stuff, thanks a lot!